For more than two centuries, from 1598 to 1882, the 1,600-mile

long El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro [“The Royal Road of the Interior”] was

the main line of communication and trade between the Spanish government in

Mexico City and its distant frontier outpost of New Mexico and its Capital City

of Santa Fe. Literally everything the

people of New Mexico needed that they could not produce themselves had to be

transported over this vital link to the outside world.

So to have

an historical connection, however tenuous, to this route without which New

Mexico would not be what it is today – would be pretty cool. So today’s question is, “Did El Camino Royal

pass through what today is called Rancho Viejo?” – the 23,000-acre (39 square mile)

parcel of land in southern Santa Fe County, which contains the HOA community in

which Marsha and I now live.

A definite

“yes” is what I am hoping for. But I

will certainly settle for a “possibly could have.”

In 1582 Fray

Bernardino Beltran and Antonio de Espejo led an expedition to New Mexico in search

of Fray Agustin Rodrigues and his fellow priests who one year earlier had gone

north from Mexico to explore the region traveled initially by Vasquez de

Coronado in 1540. Many of the priests of

the 1581 odyssey were killed en route.

Fray Rodrigues and another cleric chose to stay to try and convert the

Indians – but both disappeared and Beltran and Espejo failed to find any traces

of either of them. The report of Beltran’s and Espejo’s travels is credited

with the first official use of the term "La Nuevo Mexico" to describe

the area – as well as being the first to enter this region with wagons. In 1598, Don Juan de Onate followed these

wheel tracks as he traveled northward to become Nuevo Mexico’s first governor

in its initial capital at San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge, just west of

present-day Ohkay Owingeh where the Rio Chama meets the Rio Grande.

Robert J.

Torrez writes on newmexicohistory.org,

“Every two or three years, a supply train

composed of several dozen wagons loaded with supplies would head north towards

Santa Fe, nearly sixteen-hundred miles away. These sturdy, four-wheel vehicles

were pulled by teams of up to eight mules or oxen and carried food items that

were not grown in New Mexico, including sugar and olive oil for cooking as well

as welcome treats such as chocolate. Transportation of many other items of

Spanish material culture, such as paper, cloth, shoes, medicine, musical

instruments, barrels of sacramental wine, iron, gunpowder, and other supplies

needed by the mission churches and the Spanish colonists, made the royal road

an important factor in the survival of the colony.

“Finally, six months after leaving

Mexico, the caravan arrived at Santa Fe. Anxious government officials would

eagerly open leather pouches bulging with important government papers; local

citizens, eager for news from home, would inquire about mail from loved ones;

the wagons would be unloaded and the supplies distributed throughout the

province. For the next four to six months, trade goods from the missions and

settlements would be gathered in preparation for the return trip to Mexico.

Vast flocks of sheep were collected; raw wool, buffalo and deer hides, pine nuts,

salt, wool blankets, and woven stockings were carefully packed and loaded on

the wagons. Soon the caravan would begin its long trip south, completing

another cycle of trade and communication over the camino real—New Mexico's

royal road.”

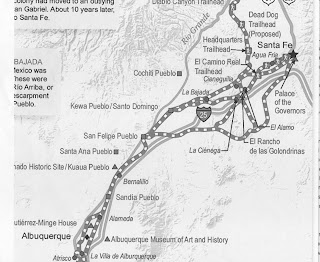

Over time

the travelers of El Camino Real developed alternate sub-routes within the

overall path.

As the

caravans approached Santa Fe there were three clear choices: “one gave

travelers the choice of scaling the basalt behemoth [of La Bajada], another

followed the Santa Fe River through the yawning canyon of Las Bocas (the

Mouths), and the third required another, longer trek around La Bajada through

the Galisteo Basin,” according to the National Park Service web site.

It is that

third option that could cause the Royal Road to find its way through the Rancho

Viejo – possibly just up the street and a few feet into the desert plains from

our actual place of residence.

A major

reason for traveling through the Basin was the presence of the eponymous

Galisteo Creek – aka Galisteo River. (We

do like to overstate the size of few water sources that we have out here.) Santa Fe residents, and visitors such as

soldiers of both the U.S. Cavalry and the Confederate Army during the 1800s would

regularly water their horses, and themselves, at the perennial stream that

flows from the eastern highlands down into the Rio Grande through

Galisteo. I learned this during a

one-on-one meeting I was fortunate enough to have with Dr. Eric Blinman,

Director of the state’s Office of Archaeological Studies. I was asking him about possible historic and

prehistoric transients through the present day Rancho Viejo property. And he pointed out that it is a “straight

shot” from “The City Different” through Rancho Viejo to the Galisteo Creek.

One Rancho

that travelers on the Royal Road most definitely did pass through was what is

today El Rancho de las Golondrinas (The “Ranch of the Swallows”) – the living

history museum in La Cienega, NM at which Marsha and I volunteer. The first owner of record for this large

property was Miguel Vega y Coca who acquired the land in the early 1700s. For

many years y Coca’s estancia (literally “stay”) was a paraje (wayside camping

spot) on the Camino Real – providing goods for trade and serving as the last stop

for travelers heading north to Santa Fe, and the first for those on the

southbound journey to Mexico. The paraje

is mentioned explicitly by, among others, the Spanish military leader and

governor, Don Juan Bautista de Anza, who he stopped there with his

expeditionary force in 1780.

Rancho

Viejo’s part on the Royal Road does not have the same written documentation as

does The Ranch of the Swallows. But sometimes

all it takes for somewhere to be considered historically significant is for it to

geographically come between two genuinely historic locales that historic people

needed to travel between – the neighborhood shortcut (“barrio atajo”) that

everybody knows about, and uses.

That

certainly sounds like a “possibly could have” to me.